Brothers Ben and Richard McReynolds have been collecting artifacts in Texas for over 50 years. Starting from a young age collecting with their mother, the two have partaken in responsible collecting and have contributed greatly to Texas archaeology. Ben is now an archaeological steward for Goliad County while his brother Richard illustrates artifacts for research and publication. This virtual exhibit showcases the many artifacts they have found across Texas, while also seeking to teach about the importance of responsible collecting, and the relationship between collectors and museums.

Diagnostics

The McReynolds collection includes artifacts that are over 10,000 years old. But how do archaeologists find out the age of an artifact?

Because some artifacts appear in narrow windows of time, archaeologists use those diagnostic artifacts to determine the relative date of other artifacts.

By recording levels in which artifacts are found and sharing their findings with other researchers, archaeologists know roughly when stone tools were created. Relative dating is inexact and can be upset by erosion and animal activity. Despite this, relative dating using diagnostic artifacts is still a useful process.

Geographic Distribution

An unusual thing about the McReynolds collection is the broad expanse of Texas geography it covers. This collection spans eleven counties, plus a few other states and even Mexico as well. The potential to study regional variances within one personal collection is remarkable.

Points are diagnostic geographically just as they are across time. Regional deviations offer insights to trade pipelines or seasonal migrations. When artifacts are found out of context, or are acquired via purchase or trade, their type may be the clue to its original origin.

Stone Tools

Scrapers are one of the original stone tool types, dating to long before the Neolithic age began. These tools were used primarily in butchering animals and removing the meat from the hides. Scrapers are one of the most commonly found tools of the Paleo era, as well as one of the more widely varied in style and shape.

Clear fork tools are the oldest and largest of the gouge type tools, being in use at least 10,000 years ago. It is believed that they were primarily used for working wood, bone, antler, hide, and plant materials.

Knives were often used without a handle. The small cutting edge was made by removing small flakes along one edge. This same process was done to sharpen it, so a knife would grow smaller over time. They have long, thin blades that are usually two-sided; this makes it a point that can more easily cut into carcasses. They also worked better for fruits and vegetables as agriculture developed. These knives may not look much like our modern-day utensils, but the design and purpose were essentially the same.

Projectile Points

Many artifacts that can be found are projectile points. These are classified into types. A type will offer clues to geographic location and dates of manufacture. Most types were made in limited regions, and for relatively short periods of time.

|  |  |

Paleolithic: 12,000-8,500 years ago St. Mary's Hall Point | Early Archaic: 8,500-5,500 years ago Early Triangular Point | Middle Archaic: 5,500-3,200 years ago Pedernales Point |

| | | |

|  |  |

Late Archaic: 3,200-2,300 years ago Marcos Point | Transitional Archaic: 2,300-1,300 years ago Ensor Point | Late Prehistoric:1,300-400 years ago Scallorn Point |

Shumla Type

Let's take a closer look at one of these point types, the Shumla. What exactly makes a Shumla point a Shumla?

Though some Shumla points may look different from each other, they all share these same characteristics:

- Triangular in shape

- Straight to convex lateral edges, frequently serrated

- Basal notches forming a rectangular stem

- Barbs, which may be long or short

- Usually well made

South Texas Shumlas are usually made of heat-treated chert, which adds a pinkish color, a slight sheen and a greasy feel. They date to the Late Archaic period, roughly 3,000 years ago, and are found in the Lower Pecos region and South Texas.

So why did early Indigenous people change the style of their projectile points? Archaeologists don't really know the answer to that. However, the rapid changes help us identify when and where the points were made.

Breakage

These Golondrina points date to about 10,000 years ago. The intact point in the top image has suffered no damage. The fragment in the bottom image shows breakage that can occur to artifacts over time. What do you think caused this break?

Materials

Lithic artifacts in Texas were usually made of chert, but archeologists occasionally find tools made of other materials. Texas Paleo-Indians had access to materials from all over North America through trade. The use of unusual materials created tools that were both beautiful and functional.

Some artifacts were made of obsidian, a deep black material formed when molten rock is cooled quickly. Its smooth, glossy texture and sharp edges make it a great material for points and cutting tools.

Early people sometimes used shells to make tools, such as scrapers for example. They also used shells to make decorative items like pennants and beads.

Do you think Native Americans created these tools with aesthetics in mind?

Ancient Lifeways

Not all surviving ancient artifacts are weapons. These artifacts provide a glimpse into the process of daily living in the past. Here, evidence of artistry alongside utility can be found: carefully woven sandals; bone awls for basketry and sewing hides; polished and engraved sticks. Also tools for the home: mano and metate for grinding their food; knives to cut meat, bone, and plant fiber; scrapers for cleaning meat from hides or bones. Were the ancient people so very different from us?

Bone Tools

Alongside tools made of stone, shell and wood, bone tools were important parts of many early toolkits. Bone tools have been in use for at least 800,000 years. Homo erectus, our hominin ancestors who lived at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania about 2 million years ago, made hand axes out of bone.

These bone awls were made by working a bone splinter to a pointed tip. These awls were used in basket-making, and for perforating animal skins to make clothing.

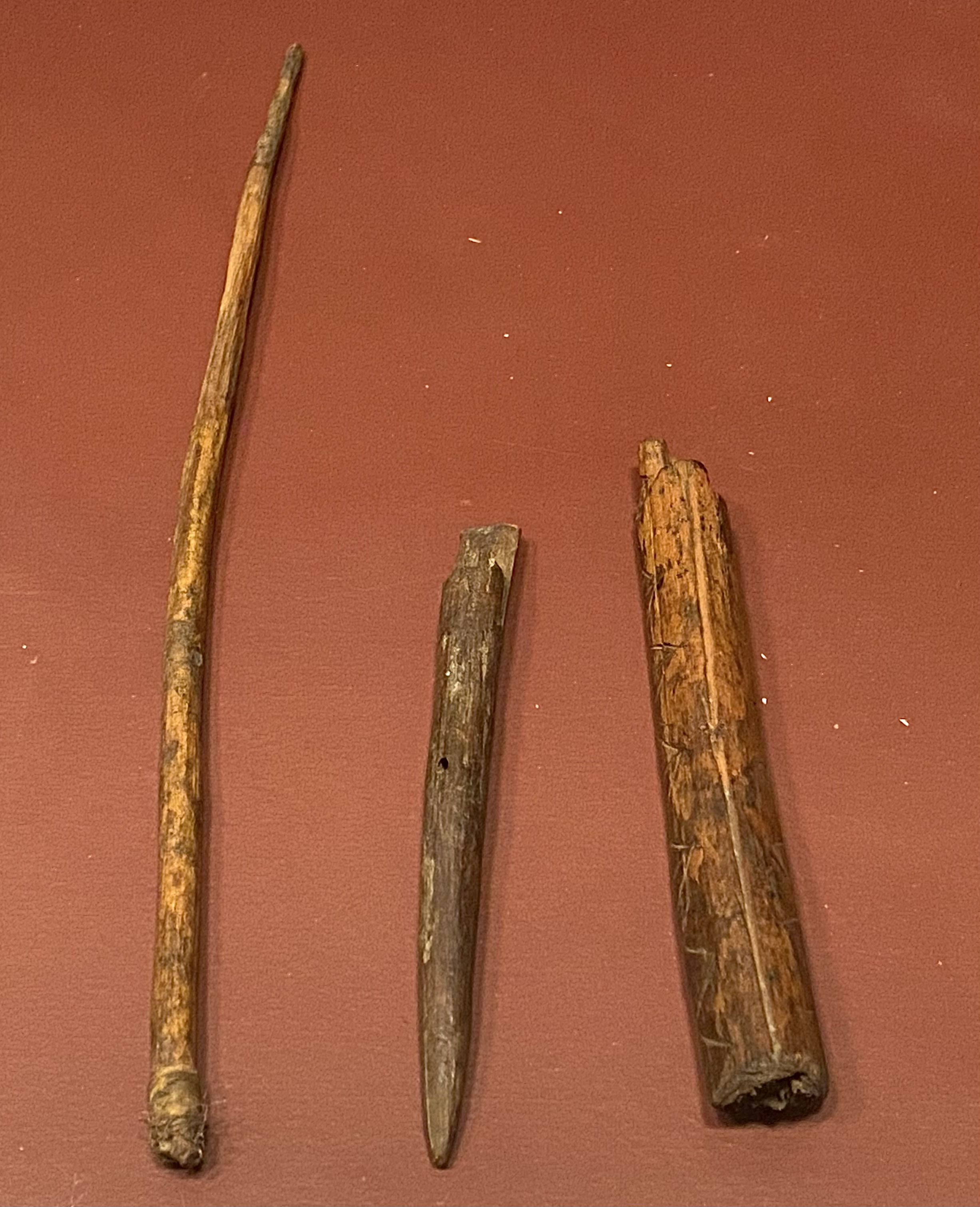

Wooden Handles

Many stone tools were hafted onto wooden handles, as points were hafted onto spears or arrows. The artifact in the center of this picture has a notch in the end and a hole drilled in the side for hafting. The item on the left still has its wrapping on the hafting end. The artifact on the right is incised with geometric designs on both sides. How do you think these were used?

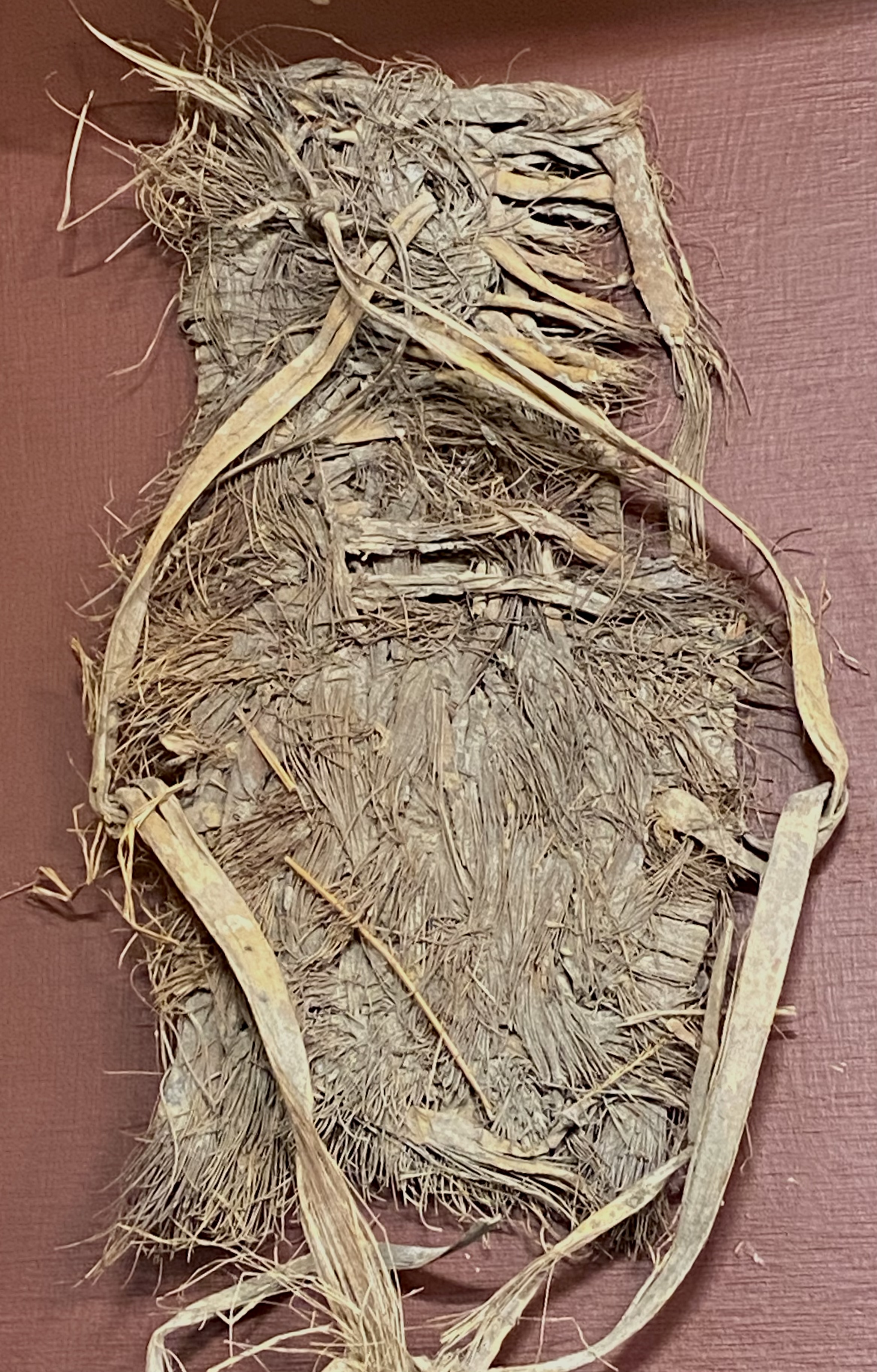

Sandals

Footwear was a necessity for the people of Archaic Texas. Walking on sun-heated ground surfaces, thorny plants and sharp limestone would have been miserable without protective footwear. Sandals, usually having padded soles and straps, were made from the fibers of lechuguilla and yucca plants.

Painted Pebbles

The ancient people of Texas painted pebbles for at least 8,000 years. Some have been found that are 8,700 years old; others were made merely 700 years ago. The purpose of painted pebbles remains unknown. Whatever their function, they likely held significance in some way as a portable entity, valued by the people who carried them.

Well-preserved painted pebbles are rare finds. Their limited numbers suggest they were held by a small percentage of the community.

Can you find the painted pebble that has an image of a man using an atlatl?

Stewardship

In 1984 the Texas Archaeological Stewardship Network (TASN) was created by the Texas Historical Commission. Its mission is to help preserve and interpret the Texas archaeological landscape. Stewards are highly trained avocational archaeologists who volunteer their time at archaeological digs.

What stewards do:

- Find, record and monitor archaeological sites

- Record private artifact collections

- Help THC archaeologists in salvage excavations

- Aid in acquiring protective designations for important sites

https://www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/projects-and-programs/texas-archeological-stewards

Click the link to learn more about the THC archaeological stewards program.

Collections and Documentation

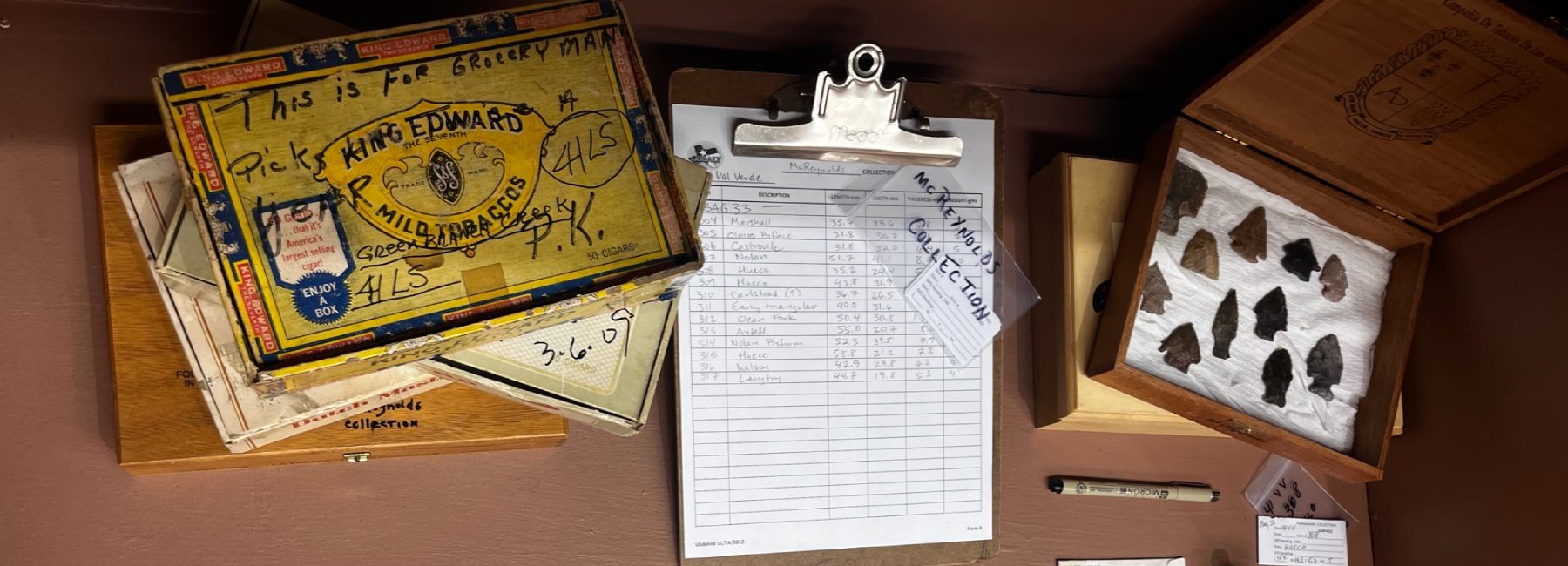

Archaeological artifacts are unique pieces of the prehistoric puzzle. Because of this, it is important that artifacts are properly collected and recorded. The real value of artifacts is in the information they provide on where, how and when people lived in the past.

Collections all begin with one item. Many collectors first used a cigar box or something similar to house their finds. Then the collection grew. One cigar box became five or ten. Perhaps it spread to a bookshelf, or the whole garage.

What makes a bunch of stuff a collection?

Curiosity!

This curiosity about who and what came before us is why we collect.

Cataloguing a collection brings order to the chaos. It can be as simple as a handwritten list of box contents, or as elaborate as a museum-style collection label for each item. Documenting the location of a find, its type, and other details of its discovery can be a great help later when time has passed and a collection has grown, making it difficult to remember each item and its story.

Museums and stewards can help private collectors document and digitize their collections as well.

https://www.museumofthecoastalbend.org/preservation

Click the link for a video interview with an avocational archaeologist about documenting.

Responsible Collecting

Collecting artifacts provides a tangible link to the past. In fact, most museums began as private collections. However, the true value of artifacts lies in what they can tell us about the past. Responsible collecting gathers information as well as artifacts.

How to collect responsibly:

- Collecting is allowed on private land only. Be sure to have the owner's permission!

- Keep records of your finds. Identify finds with unique numbers which correlate to the records in your file.

- Note the location of your finds on a map.

- Don't dig for artifacts, take surface finds only. Leave excavations to professionals and avocationals who are trained in archaeological processes.

- Valuable information is lost through improper digging.

Acknowledgements

This exhibit owes much to many.

Special thanks to Ann and Ben McReynolds for sharing family photos and stories.

Artifact illustrations by Richard McReynolds.

Virtual exhibit created by Consuelo Leos.

We are also deeply grateful to:

Bill Birmingham

CoBALT

Dr. Tom Hester

Glory Turnbull

VC Physical Plant

The Witte Museum